A Note on Schism, Donatism, and Catholicity

By Fr Jay Thomas and Fr Ron Offringa

We thought it would be prudent to begin with a short excursus on schism and Donatism. Many of these themes will be discussed throughout the series (especially in our commentary on Article 13), but some of them deserve a brief commentary at the outset

Concerning Schism

In declaring that the Anglican Communion has been reordered, there is a sensible and well-meaning critique that the Global Anglican Communion represents a schism. We will examine this critique by posing two questions:

First, what is the catholic tie that binds the Anglican Communion together?

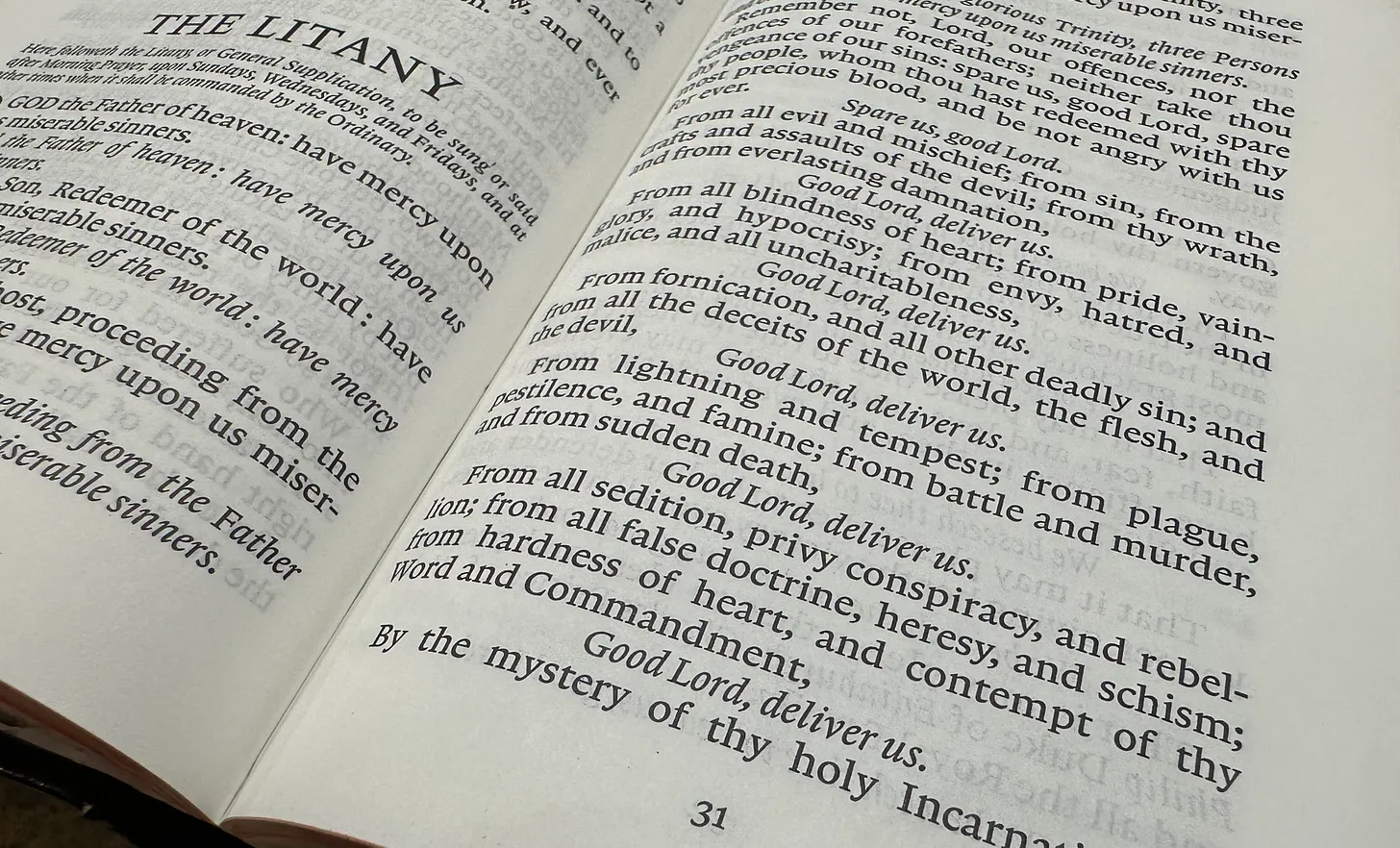

That tie has always been a common rule of faith, worship, and polity. Interestingly enough, this is most clearly seen in the origins of the Anglican Communion upon the separation of the Episcopal Church (USA) from the Church of England after the American Revolution. As stated in the Preface to the first American Prayer Book, “when in the course of Divine Providence, these American States became independent with respect to civil government, their ecclesiastical independence was necessarily included.” And yet, although independent, it was understood that a common tie bound them together. That tie was not the Archbishop of Canterbury—indeed, the Archbishop recused himself from consecrating the first Bishop of the American Church—but rather it was all “essential points of doctrine, discipline, and worship.”

Second, what is the Anglican Church’s raison d’être contra the Church of Rome?

It was that the catholic faith and catholic church is not defined by one’s communion with an individual (in this case, the Bishop of Rome), but rather is defined by the common faith and practice of the Church. In the English Reformation we asserted that to remain Roman was to cease to be Catholic, because the Roman See had so clearly harmed the faithful through her additions to the sacred deposit of the faith. In a similar way, when the See of Canterbury persists in error altering the doctrine and discipline of the Church, we have no choice but to continue in the faith while she departs.

There is a profound irony in claiming an intrinsic tie between Anglican identity and the See of Canterbury to such an extent that any separation from that unity is schism. In this Canterbury-centric model of ecclesiology the Archbishop of Canterbury would become a figure much more akin to the Pope. Were we to adopt such a model, where connection to a See trumps faithful doctrine and practice, we ought all return to Rome and submit to her errors. If, however, catholicity is centered around apostolic succession, biblical doctrine, and godly discipline, then we must seek true catholic unity around the truth rather than false unity around a See.

To say that the catholic faith can be defined doctrinally is not to lapse into a confessional denominationalism which exists perpetually in schism; rather, it is to acknowledge that the faith “once for all delivered to the Saints” (Jude 3) is a thing which can be named, identified, and believed. As such, when churches forsake the catholic faith, we acknowledge them to be in schism. It would be preposterous to claim that the Arian Churches, which existed for centuries after the Council of Constantinople in Northern Europe and the Iberian peninsula, were the true catholic church. No, they were heretics and schismatics. Why? Because they had abandoned the catholic faith upon which the unity of the Church was made manifest and had been summarily anathematized for it. Catholic unity is a unity forged doctrinally and lived out conciliarly.

Concerning Neo-Donatism

But even if we are not in schism through steadfastly maintaining the orthodox faith, are we in danger of repeating the error of the Donatists who rejected the validity of the Sacraments of the Catholic Church when priests and bishops failed in the fiery trials of persecution? Are we guilty of attempting to limit the scope of God’s grace?

While we will thoroughly address the Neo-Donatist critique in our commentary on Article 13, it is worth noting from the beginning of this series that the concern of the Donatists was primarily one of moral, not doctrinal, failure. The Donatists, and the Novatians before them, were unlike heretical groups such as the Arians, Macedonians, Paulianists, and others insofar as their schism was grounded in a desire for moral, not doctrinal, purity.

Given the significant departure of revisionist provinces within the communion to bless sin, to deny the faith, and to refuse correction of doctrinal error, there is a real concern that we no longer share the same faith, which is a very different issue than the one facing the Donatists. Rather, the modern situation is more akin to the relationship between the early church and the libertine gnostics (e.g. the Carpocratians).

Catholic Unity

We give thanks for the witness and action of primates and bishops around the globe—most notably in the Global South—who took the courageous stand in 2008 to preserve both the catholic faith and catholic unity through their formation of GAFCON and ultimately the ACNA. Through their sacrificial actions we have never been in schism. Indeed, their actions were the clearest demonstration of the successors of the Apostles acting as they were called to do: unflinchingly defending the faith as icons of the unity of the Church. Thereby, we rejoice in our inheritance of this common faith, common worship, and pursuit of common order within Christ’s Church. May he give us grace to maintain it just as courageously.