Article 4. The Authority of the Thirty-Nine Articles

by the Reverend Kyle Clark

Article Four

We uphold the Thirty-nine Articles as containing the true doctrine of the Church agreeing with God’s Word and as authoritative for Anglicans today.

Richard Hooker, following Thomas Aquinas, calls theology “the science of things divine.”1 Theology, however, is never for the mere purpose of knowledge. Rather, it leads us into greater love and devotion to our God, and it fuels the prophetic ministry of the Church. Therefore, when done with a proper heart, theology is never a distraction from the mission of the Church. It is part of the mission of the Church. To form such a heart we turn to the Holy Scriptures, the source of our authority, to hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them. Having treasured the words of sacred Scripture, we speak theology, “for out of the abundance of the heart [our] mouth speaks” (Luke 6:45).

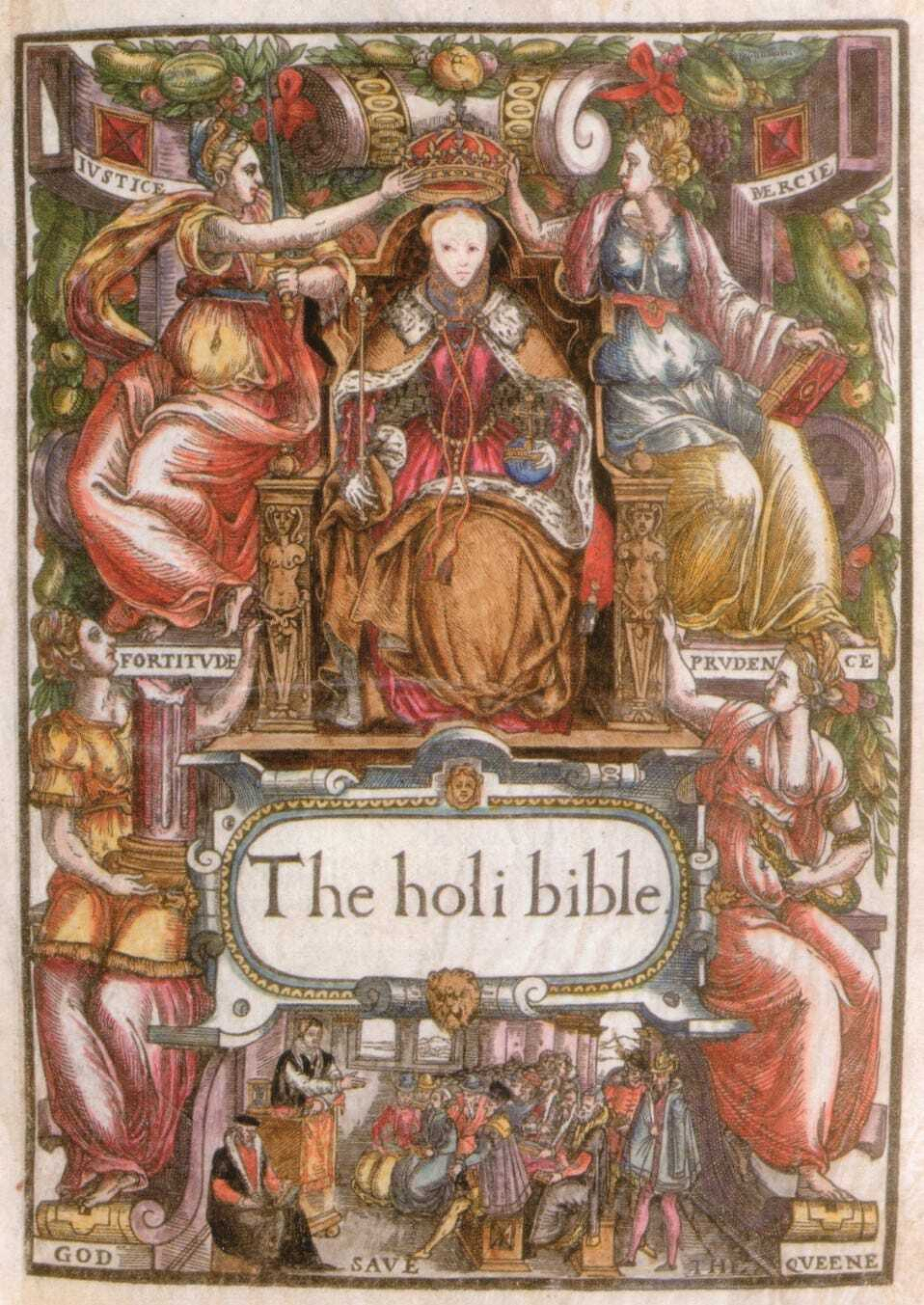

The formative output of faithful Divines reading and digesting Scripture in the early years of the English Reformation is the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. The Jerusalem Declaration proclaims that these Articles “contain the true doctrine of the Church agreeing with God’s Word and as authoritative for Anglicans today.” What, then, does it mean for the Thirty-Nine Articles to contain the true doctrine of the Church, and what does it mean for them to still be authoritative today, these 450 years later?

Clarification Formed Out of Controversy

Ideally, all Christians would read the Scriptures in the same way, guided by the same Spirit, and the truth would be clear to all. Sadly, as Church history has shown, we have struggled to be of the same mind regarding the Scriptures. This has happened not only because of our own immaturity,2 but because there are tares sown among the wheat in the Church who have crept in unnoticed with darkened minds, ever learning but never arriving at the truth.3

When Christians disagree about the interpretation of Scripture, controversy arises. When the early Church debated the nature of God, the Trinity, and Jesus Christ, they were debating Scripture, but they disagreed vehemently. As this process continued—and as we discussed in our commentary on Jerusalem Declaration Articles Two and Three—they eventually called councils to help bring clarity to the debate. These early ecumenical councils produced creeds and provided theological clarifications. They gave us our rule of faith to digest the plain and canonical sense of the Scriptures, which in turn produces faithful theology.

As new issues arise, new and more precise clarifications are needed. Cultural assumptions change. Errors creep into the Church. Doctrines that had long been clear become muddy. These new clarifications are not, strictly speaking, new ideas. They are a renewed affirmation of what Scripture has always said and the Church has always believed. So, at the time of the Reformation, when new controversies and issues had arisen, such as the authority of Scripture, justification, faith, and good works, formulating clarifications based on the Scriptures as read by the ancient Fathers was needed. This is where the Thirty-Nine Articles fit into the Anglican tradition.

Containing the True Doctrine of the Church

The Articles, as an official clarifying definition of the Anglican Tradition, aligned the English Church as a moderate Reformation against the errors of the Church of Rome on one side and the radical reformers on the other. None of the English Reformers saw themselves creating a new Church or developing a new theology. They were recovering—as their rightful inheritance—the Catholic faith of the Early Church.4

From the very outset of the Articles, the authors place the Anglican tradition as an heir of the Church Catholic by affirming the faith of the Councils and the Creeds, and this work of recovering our inheritance continues into the rest of the Articles. In several places they explicitly reference Church Fathers (e.g. St. Jerome in Article VI and St. Augustine in Article XXIX), and in many other places they are clearly drawing on Patristic theology. In the other canonical writings of English Reformers enshrined in the Book of Homilies as well as their own works defending the faith, they consistently quote from the Church Fathers.5

The argument of the English Reformers, then, is that the theology expressed in the Thirty-Nine Articles is the theology of the Patristic Fathers.6 It is the true doctrine of the Church as it has been passed down by the Apostles to the bishops through the ages. The controversy of the Reformation helped to clarify and define it, not invent it.

This does not mean that the Church Fathers consistently utilized the same terminology and spoke the same way as the Reformers did. The same can be said of the ante and post-Nicene Fathers. Circumstances and controversies change, but there remains a consistent theological throughline that runs all the way from the Apostolic Fathers through the English Reformers in the Thirty-Nine Articles. Each generation speaks successively in greater clarity with one voice, receiving the fulfillment of Christ’s promise that the Spirit would lead us into all the truth (John 16:13) so that we might speak the true doctrine of the Church.

Agreeing with God’s Word

The Reformers, however, are clear: these doctrines are not true because they agree with the Fathers, but because they faithfully declare the plain and canonical sense of the Scriptures—as the Fathers themselves sought to speak.7 Articles XX and XXI bind the authority of the Church and its Councils to the authority of Scripture. The Church may not “ordain any thing that is contrary to God’s Word written, neither may it so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another.” The decrees of Councils only have strength and authority if “it may be declared that they be taken out of Holy Scripture.” This is reflected in Article VIII, where the Creeds are received, “for they may be proved by most certain warrants of Holy Scripture.”

This commitment underpins the rest of the Articles. When they address the controversies of their day, the clarifications they provided are grounded in Scripture, and when needed, they look to Natural Law and the Church’s tradition to buttress and solidify their clarification, a hermeneutical framework described by Hooker (a contemporary of the Articles).8 The Reformers were not reading Scripture in isolation to produce the Thirty-Nine Articles. Rather, they sought the plain and canonical sense of the Scriptures while being respectful of the Church’s historical and consensual reading.

Authoritative Today

The Jerusalem Declaration receives the Thirty-Nine Articles as authoritative for Anglicans today, but how do they function authoritatively among us?

Let us use the Creeds as an example to explore this authoritative relationship. The Thirty-Nine Articles receive the three historic Creeds of the Church and then the Jerusalem Declaration clarifies for us that these Creeds function as our Rule of Faith. While these doctrinal statements from the first five centuries of the Church are not the inspired Word of God, they are the authoritative guardrails which help us ensure we are interpreting and understanding the Word of God rightly. In a similar manner, the Thirty-Nine Articles have become similar authoritative guardrails to our faith; they provide checks and balances to our personal pious opinions and prerogatives.

These checks are not only for personal opinions, though, indeed, the current contention separating the Canterbury Communion from the Global Anglican Communion boils down to whether or not Article XX of the Thirty-Nine Articles remains authoritative. Article XX states:

The Church hath power to decree Rites or Ceremonies, and authority in Controversies of Faith: And yet it is not lawful for the Church to ordain any thing that is contrary to God’s Word written, neither may it so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another. Wherefore, although the Church be a witness and a keeper of holy Writ, yet, as it ought not to decree any thing against the same, so besides the same ought it not to enforce any thing to be believed for necessity of Salvation.

While all Anglicans agree that the Church has authority in controversies of Faith and is the “keeper of holy Writ,” the Canterbury Communion has turned a blind eye to rife examples of Anglican Provinces “ordaining things contrary to God’s word written.” The blessing of same-sex relationships, sanctioning a pro-abortion ethic, and the ordination of women to the presbyterate are practices which stand openly contrary to the plain and canonical sense of Scripture. Moreover, the defenses of these contra-biblical practices often rely on various interpretations of Scriptural prooftexts (e.g. Acts 10:9-48, Genesis 2:7, and Galatians 3:28, respectively) which all stand in open contradiction (“are repugnant to”) to other passages in scripture (e.g. 1 Corinthians 6:9, Luke 1:41, and 1 Timothy 2:12, respectively).

While no neat set of proof-texts necessarily establishes a given doctrine, arguing that the Church has authority in controversies of faith to favor one section of Scripture over another openly repudiates the teaching authority of Article XX. By implicitly rejecting the authority of the Thirty-Nine Articles the Canterbury Communion has departed from the magisterial tradition of the church. Conversely, affirming the authoritative status of the Articles binds the Global Anglican Communion not to personal opinions formed by the spirit of the age but to the faithful witness and keeping of holy Writ that has gone before us.

Conclusion

The Thirty-Nine Articles emerged out of the doctrinal debates of the Reformation, but they are not limited to them, just like the doctrines of the Creeds are not limited to the early Church. Both the Creeds and the Thirty-Nine Articles authoritatively declare the true doctrine of the Church in a way that remains relevant today because both agree with God’s Word. Therefore, we continue to hold them as authoritative guardrails to our faith.

Moreover, the work of theology remains essential to the mission of the Church. New challenges have arisen in the Church since the time of the Thirty-Nine Articles, challenges that the Jerusalem Declaration seeks to confront. By standing on the solid ground of “the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) as received in the Thirty-Nine Articles, orthodox Anglicans are best equipped to apply the plain and canonical sense of Scripture to these challenges in a manner that is consistently respectful of the historic interpretation of the Church.

↩︎ (On the Jerusalem Declaration)

-

Richard Hooker, Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, III.8.11 ↩︎

-

Matthew 13:24-30; Ephesians 4:18; Jude 4; 2 Timothy 3:1-7 ↩︎

-

“Further, if we do shew it plain, that God’s holy gospel, the ancient bishops, and the primitive church do make on our side, and that we have not without just cause left these men, and rather have returned to the apostles and old catholic fathers; and if we shall be found to do the same not colourfully, or craftily, but in good faith before God, truly, honestly, clearly, and plainly; and if they themselves which fly our doctrine, and would be called catholics, shall manifestly see how all those titles of antiquity, whereof they boast so much, are quite shaken out of their hands, and that there is more pith in this our cause than they thought for; we then hope and trust, that none of them will be so negligent and careless of his own salvation, but he will at length study and bethink himself, to whether part he were best to join him. Undoubtedly, except one will altogether harden his heart, and refuse to hear, he shall not repent him to give good heed to this our Defence, and to mark well what we say, and how truly and justly it agreeth with Christian religion.” John Jewel (1522-1571), An Apology of the Church of England, Davenant Press, pg. 14. ↩︎

-

E.g., The Homily on the Salvation of Mankind by Only Christ our Saviour from Sin and Death Everlasting: “These and other like sentences, that we be justified by faith only, freely, and without works, we do read ofttimes in the most best and ancient writers. As, beside Hilary, Basil, and St. Ambrose before rehearsed, we read the same in Origen, St. Chrysostom, St. Cyprian, St. Augustine, Prosper, Oecumenius, Photius, Bernardus, Anselm, and many other authors, Greek and Latin.” ↩︎

-

“The Religion of the Church of England, by Law established, is the true Primitive Christianity; in nothing new, unless it be in rejecting all that novelty which hath been brought into the Church. But they [i.e. the Roman Catholics] are the cause of that. For if they had not introduced new Articles, we should not have had occasion for such Articles of Religion as condemn them. Which cannot indeed be old because the doctrines they condemn are new, though the principle upon which we condemn them is as old as Christianity,–we esteeming all to be new, which was not from the beginning…” Simon Patrick (1626-1707), The Second Note of the Church Examined, viz. Antiquity, pp. 55f. as quoted in Anglicanism, ed. More and Cross. ↩︎

-

Cf. “Thus did the holy fathers alway fight against the heretics with none other force than with the holy scriptures.” John Jewel (1522-1571), An Apology of the Church of England, Davenant Press, pg. 16. ↩︎

-

Richard Hooker, Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, V.8.2 ↩︎